Daniel Okrent’s 2004 New York Times Column Even More Relevant Today

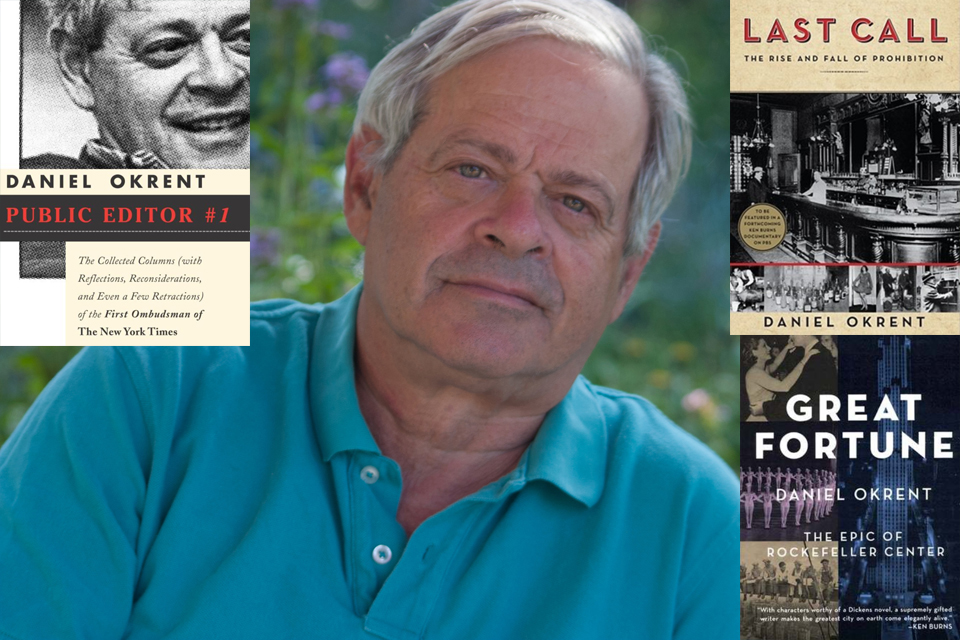

Editor’s Note: In October 2003, Daniel Okrent was named the first public editor for the New York Times (NYT) following the Jayson Blair scandal. Okrent served in that position until May 2005. In June 2004, he wrote the piece below about the overuse and misuse of ANONYMOUS SOURCES. Given the current howling about anonymous sources, the constant declarations about “fake news,” and calling the press the “enemy of the people” during the Trump era, I thought it would be worthwhile to reconsider Okrent’s 2004 column and a follow-up comment he made in Public Editor Number One, a collection of his NYT columns published in 2006. Okrent is also the author of Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center, which was a finalist for the 2004 Pulitzer Prize in history, and Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, which received the Albert J. Beveridge Award for Year’s Best Book of American History, 2011. His new book, The Guarded Gate: Patrician Bigots, Eugenic Science, and the Campaign to Keep Jews, Italians, and Other “Inferiors” Out of the U.S., will be published by Scribner in May, 2019.

An Electrician from the Ukrainian Town of Lutsk

By Daniel Okrent, June 13, 2004

I KNOW that’s an odd headline, but it’s not original with me. I lifted it from reporter Richard Bernstein’s identification of an otherwise anonymous man he interviewed for an article published in The Times on April 25. This is not meant to criticize Bernstein: I don’t know any electricians from Lutsk, but I would rather have one of them in my mind’s eye than anyone identified as ”an analyst,” ”an expert,” ”a lawyer involved in the case,” ”a senior State Department official,” ”a Democratic strategist” or any of the other standardized obfuscations that can make a morning with The Times so exasperating.

Last winter, I met Jason B. Williams, a New York University journalism student who was writing his master’s thesis on unidentified sources in The Times. (I copped the idea for my headline from the title of his thesis, taken from another Times ID: ”A Blue-Eyed Man With a Flowing Beard.”) By reading every bylined A-section news story published in December 2003, Williams determined that 40 percent of the articles invoked at least one anonymous source, that the average day’s paper brought 36 such sources into the reader’s home and that more than half of these people were identified, at least in part, as ”officials.”

After The Times promulgated a revised policy on the use of anonymous sources in February (it’s a fascinating document — read it at nytco.com/company-propertiestimes-sources.html), I commissioned Williams to conduct a similar study in April, to help me determine if the new policy had had any measurable effect. As it happens, the most important part of the new policy involves something that cannot be checked independently: a requirement that a ranking editor must know the identity of a reporter’s unnamed source. The one exception involves ”crucial issues of law or national security in which sources face dire consequences if exposed”; only executive editor Bill Keller can waive the rule. (So far, Keller told me the other day, no one has asked him for a waiver.) Allan M. Siegal, the paper’s standards editor, says that his frequent spot checks have detected ”clear improvement in the identification of sources to editors” since the policy went into effect on March 1.

But Siegal also said, ”I don’t mind conceding that habits die hard,” which I regard as an explanation of why readers are still being asked to do what they should never have to: take things on faith. As the policy states, the use of unidentified sources requires the paper to ”accept an obligation not only to convince a reader of their reliability but also to convey what we can learn of their motivation.”

Williams’s numbers (which show a slightly greater rate of anonymous quotation than his December study) and my own reading of the paper tell me this obligation has not been met. In April, barely 2 percent of stories citing anonymous sources revealed why The Times granted the request for anonymity. Only 8 percent of unidentified sources were described in a meaningful fashion. (”Congressional official” is not meaningful; ”Congressional staff member who works for the minority leader” is.) Just last Monday, ”The Split Between Disney and Miramax Gets a Little Wider,” by Sharon Waxman and Laura M. Holson, was built on information provided by ”close associates,” ”friends and executives” who had talked to Disney C.E.O. Michael Eisner, ”two people who attended” a Disney board retreat, a ”person who attended” a dinner with Eisner, ”a senior Disney executive,” ”Hollywood experts” and ”analysts.”

I would love to know how much faith readers put into this kind of sourcing (and I have a feeling you’ll tell me). Personally, I’m feeling pretty comfortable with the story, because neither Disney nor Miramax, which are not afflicted with timidity, has called me to say the story was factually wrong. But this doesn’t do much good for the reader who is not granted the questionable privilege of daily contact with angry story subjects.

Electricians from Lutsk may be innocent bystanders, but most anonymous sources are not. They have many different motivations, but I doubt we’ll ever see the paper cite what must be the most common one: deniability. If your name isn’t attached to something that turns out to be wrong or embarrassing, you never have to take the heat for it.

Welcome, in other words, to Washington, where ”senior State Department officials,” ”White House aides” and other familiar wraiths can say what they want without ever being held accountable for it. Their invisible domain extends overseas as well. Last Tuesday, in ”Nine Iraqi Militias Are Said to Approve a Deal to Disband,” by Dexter Filkins, one sentence began, ”Two American officials, who spoke to a group of reporters on the condition of anonymity. ” This was no whispered conversation in some Baghdad back alley; Filkins told me there were roughly 40 people in the room when the officials spoke. All of them, of course, knew very well who the officials were. Their editors did, too. And there’s no question the officials’ colleagues in the government knew as well. In other words, everyone knew — except the paper’s readers.

I can’t find Filkins or his editors guilty for playing along with this dishonest practice; reporters must accept the rules to get the information. Times editors in fact tried to make an issue of such ”background briefings” during the Clinton administration (Democrats are as adept as Republicans at this game). Andrew Rosenthal, the Washington editor at the time, instructed reporters to ask that everything be put on the record. When this request was invariably declined, the reporter was expected to ask why. The next part of the script had the reporter declare that The Times would therefore not participate in the briefing. ”I dropped it after a while,” Rosenthal told me last week, ”because the rest of the press corps ridiculed our reporters.” And because it just didn’t do any good.

BUT The Times could do some good for its readers in other ways. For one thing, it oughtn’t have to wait for me to whine about it to let readers know how official Washington plays its cynical game. The paper may have to play by the rules, but that doesn’t mean these rules can’t be explained to readers. They’re the ultimate victims — citizens whom both the journalists and the officials presumably represent.

The paper could certainly make a stronger effort to explain sources’ motivations. Why did all those mysterious people tell Waxman and Holson about Eisner’s thinking? Were they floating balloons in his behalf? Were some of them winking at the Disney board, alerting them through The Times that Eisner might be susceptible to pressure on a deal? Did any have a personal interest in the Disney stock price?

The paper could also require its reporters to rephrase the implicit contract with sources so that it says, ”If you lie to me, I will no longer protect your identity.” After I raised this idea in my May 30 column, I was asked whether it would be fair if sources didn’t know this was the deal. Well, make it an explicit part of the deal — every anonymity deal — up front. And who’s to say whether a comment is in fact a lie? This shouldn’t be a problem: if I trust a reporter to protect my name in the first place, isn’t it logical that I would trust her to make that determination as well?

The easiest reform to institute would turn the use of unidentified sources into an exceptional event. They’re necessary, of course, in reporting on national security; they’re inescapable in reporting on certain foreign policy issues (diplomats, being diplomatic, almost never allow their names to be used). I’ll even grant that knowing what Disney is or is not doing with Miramax justifies reliance on unidentified sources.

But in last Tuesday’s paper alone, anonymous testimony enabled readers to learn that senators examining the intelligence community intend to concentrate on looking forward, that no two large public events in Washington can be planned in the same fashion, that Barbra Streisand expects hoteliers to scatter rose petals in her bathroom and that many people inside government worry about political consultants becoming lobbyists.

I do not feel the earth shaking.

Finally, it’s worth reconsidering the entire nature of reportorial authority and responsibility. In other words, why quote anonymous sources at all? Do their words take on more credibility because they’re flanked with quotation marks? If Waxman and Holson had written their article in their own voice, eschewing all blind quotes and meaningless attributions and making only the assertions they were confident were true, we could hold someone responsible for the accuracy: not the dubious sources, but the writers themselves. Isn’t that the way it ought to be?

Follow-up comment published in Public Editor Number One, a collection of Okrent’s New York Times columns, 2006.

This piece may have added only one more word to the industry’s now-raging conversation on the topic of anonymous sourcing, but there’s no question in my mind that this is the journalism conversation that matters more than any other these days. The Dan Rather report on George W. Bush’s military record, the Valerie Plame leak case (and Judith Miller’s subsequent jailing and the Time’s subsequent failing), the controversy over the Time’s reporting on the NSA wiretap program – all of them hinged on anonymous sourcing. And all of them provoked discussion in the Newsroom regarding when the practice is appropriate.

My summary view is that, in new reporting, the use of an anonymous source must pass two tests: Is what I’ve learned truly important? And, is there no other way – no on-the-record way – to convey it to my readers?

It’s also worth bearing in mind the words of David Rosenbaum. Rosenbaum, a veteran Times reporter who was murdered in a Washington street robbery in January 2006, was as decent and generous a human being as one could possibly imagine; he also was an aggressive, determined reporter who broke many important stories throughout his long and distinguished career. Shortly after Rosenbaum’s death, former Times Washington editor Adam Clymer told The New York Observer that Rosenbaum had come to believe that “promises of confidentiality were given much too casually. He said you needed to protect the City Hall janitor who exposes corruption, but not political gossips.”

Copyright © 2006 by Daniel Okrent and the New York Times. Reprinted with permission of the author.