Stephen Kinzer:

Our Man in Istanbul, Berlin, and Nicaragua

Stephen Kinzer is an award-winning foreign correspondent who has covered more than fifty countries on five continents. Stephen worked at the New York Times for more than twenty years, serving as bureau chief in Turkey, Germany, and Nicaragua. He previously worked as Administrative Assistant to Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, and then as Latin America correspondent for the Boston Globe. Stephen has written nine books on foreign affairs.

The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire (Henry Holt & Company, 2017), his most recent book, “Presents a revealing piece of forgotten history. Kinzer transports us to the dawn of the twentieth century, when the United States first found itself with the chance to dominate faraway lands. That prospect thrilled some Americans. It horrified others. Their debate gripped the nation.

The country’s best-known political and intellectual leaders took sides. Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and William Randolph Hearst pushed for imperial expansion; Mark Twain, Booker T. Washington, and Andrew Carnegie preached restraint. Only once before―in the period when the United States was founded―have so many brilliant Americans so eloquently debated a question so fraught with meaning for all humanity.

All Americans, regardless of political perspective, can take inspiration from the titans who faced off in this epic confrontation. Their words are amazingly current. Every argument over America’s role in the world grows from this one.” (Books & Books).

On Monday, February 27, 2017, at Books & Books in Coral Gables, Kinzer gave a rousing talk about the role of United States in the world — a debate that began in 1898, and is still going on today. Needless to say the quality of discourse in 1898 was considerably higher and more eloquent than now.

Kinzer’s other riveting books include: The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War; Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala; Blood of Brothers: Life and War in Nicaragua; Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds; Reset: Iran, Turkey, and America’s Future; A Thousand Hills: Rwanda’s Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It; Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq; and All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror.

Kinzer is also a dynamic and engaging speaker. I first got to know him in 2008, when he and Harvard professor Noah Feldman enthralled a packed lecture hall at Northeastern University as part of the “Advice to the Next President” series, the fall semester topic in the Open Classroom, cohosted by Barry Bluestone and Michael Dukakis. After the lecture, the speakers and ten guests went to dinner at Brasserie JO, where I established my six degrees of separation connections with Stephen, and began an inexhaustible conversation about world events, politics, and the nature of the American people.

Raymond Elman: Where were you born and where did you grow up?

Stephan Kinzer: I was born in New York City. My parents, Ilona and Mike, lived in Greenwich Village in the ’50s and spent summers in Provincetown, Massachusetts. We settled in Truro on the northern tip of Cape Cod, because we were already familiar with the Outer Cape, having spent all our summers there. My mother became a schoolteacher at Nauset Regional High School. Later she went to graduate school at Harvard, so we moved to Boston where I went to Brookline High School. My mother, Ilona, was also an actress and became very much a part of the Truro cultural life. She acted in Greenwich Village and worked with José Quintero, who was a famous director at that time. Ilona and my father were very into the offbeat cultural scene in Greenwich Village—I guess you’d call it “beatnik”—and a lot of that scene migrated to Provincetown and Truro in the summer.

While I was a student at Truro Central School, I was also a newspaper boy. When I look back on it, that was the beginning of my career in journalism. Every day after school, I would pick up the afternoon paper, which was then the New Bedford Standard Times, at the Pamet Grocery Store. I’d get on my bike and deliver the paper along the roads of Truro.

RE: Did you read the newspapers?

SK: I did. I was always interested in news. My parents never had a television. When there was something of major interest, we would go next door to watch it on our neighbor’s television. I still remember watching the press conference at which President Kennedy announced the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba.

I learned other journalistic lessons in Truro too. My career as a newspaper boy started in September, when the school year began. The first year, I still remember that to my amazement I had to deliver papers on Thanksgiving Day. I didn’t think they would have newspapers on Thanksgiving Day. There was even a newspaper on Christmas day. I began thinking that news must be something fascinating, because it doesn’t respect the calendar.

RE: What did your father do?

SK: My father, whose byline was H. M. Kinzer, was an editor for Popular Photography magazine for many years. He was also a student of literature. When I was born, my father was writing his master’s thesis at Columbia University on James Joyce, and I am named after Stephen Dedalus.

RE: When you moved to Truro for the fourth grade, did you become aware of people in the literary and visual arts community, and did you have any interactions with them that were influential on you?

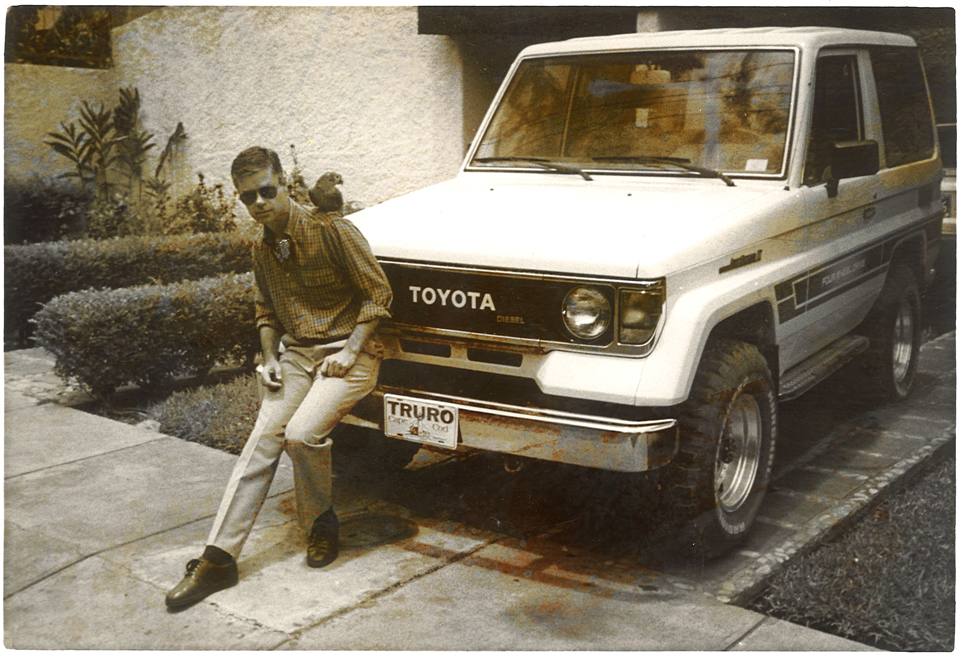

SK: My mother was very connected with those people. Certainly, when I was a little kid in Provincetown in the summer, I met many people that I now recognize as being big-time Provincetown artists of that period. Most of the artistic people I met as a kid were visual artists, so they were not people I came across later in journalism. But I always carry a memory of the Outer Cape as the cultural part of my background. In fact, there’s a story in my Nicaragua book about me pulling up to a road block and a soldier writing down my license-plate number, not realizing that the plate was not a real license plate, but just one of those souvenir plates that says “Truro” on it and has a little lighthouse. That got me through the road block. He wrote the word “Truro” in some Central American police log and made a sketch of the lighthouse. I still have the license plate in my living room.

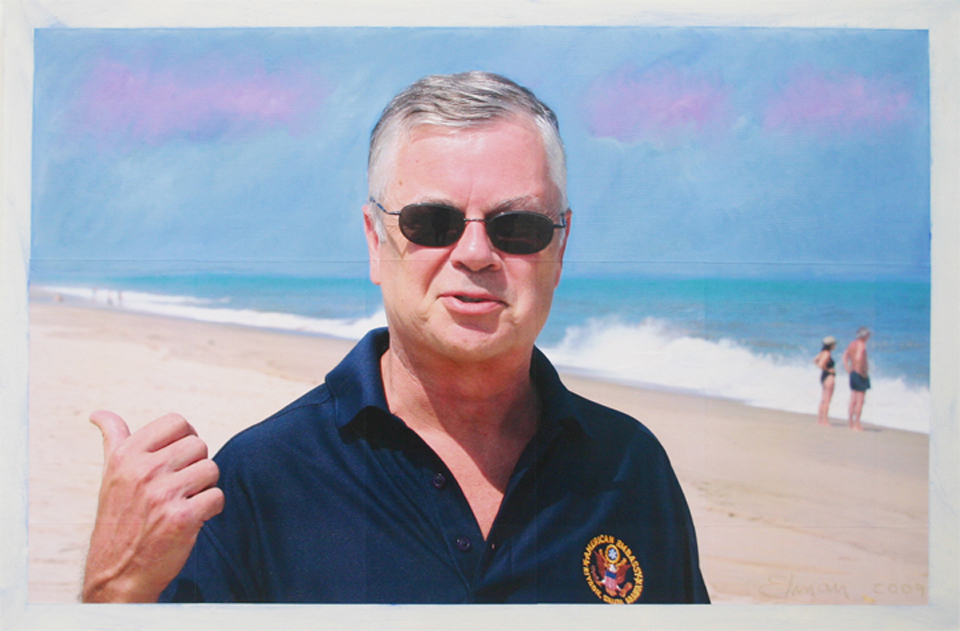

Stephen Kinzer outside the “New York Times” bureau in Managua with the bureau’s parrot.(note Truro license plate), 1986

RE: That could only happen before the digital age. Your book about the Dulles brothers is primarily about the Cold War and the 1950s. What was Truro like through the lens of the Cold War?

SK: The Cold War was at its peak when I was growing up in Truro.

RE: I grew up in the suburbs of Cincinnati and graduated high school in 1963. I remember “Duck and Cover,” instructions to schoolchildren in case of a Russian atomic bomb drop. I also remember a high-school course on Communism where the teacher began by saying, “I’m not going to fill you full of anti-Communist propaganda and tell you that Communists are evil boogie men,” and then she proceeded to do exactly that. Did you grow up with the same sort of Communist paranoia in Truro?

SK: During the Cold War, Truro was a special place because it had a U.S. air force base. It’s a bunch of broken-down buildings looking for a purpose now, but that was a high-security area when I was a kid. We were very conscious of it. In my class at Truro Central School there were always kids whose parents lived at the base. Our little-league coaches in the summertime tended to be air force guys, whose kids were also on the team. The base was a conduit to reality for us.

When the Cold War was at a peak, we bought into that paradigm, and, wanting to be on the front line, we kids convinced ourselves that when and if the nuclear exchange with the Soviets began, one of the very first targets for the Soviets would be the North Truro Air Force Base. We were also taught at Truro Central School, as schoolchildren were taught across America, that we should have bomb shelters at home. I told this to my mother, but she did not take it seriously. I tried to impress upon her the urgency and became increasingly frustrated that she didn’t see much need for a bomb shelter at our house. Finally, in rising anger, I said to her, “What are you going to do when the Russians invade?” And she said, “Maybe I’ll invite them in for tea.” This was the moment when I decided that my mother was an idiot, and that I had to take responsibility for the protection of our family. So I stashed several cans of food and some forks and knives into the crawl space of our basement. They’re probably still down there today.

RE: Now contrast your Truro Central School Cold War preparedness with Truro as a hotbed of Communists. From the moment I arrived in Provincetown in 1970, I heard stories about active Communists living in the hills of Truro. Did you know any of them?

SK: Yes, but not in the 1950s. After finishing six years as the Times bureau chief in Nicaragua, I took a year off and came home to Truro to write a book about my experiences there–that was “Blood of Brothers.” It was during that year, 1989, that I met Steve Nelson, who had just finished building himself a house. I used to go over and sit with him and his wife Margaret in the evenings. He would tell stories about the Spanish Civil War, his experiences slipping into Nazi Germany on secret missions, his union organizing, his arrests, his trials, and his final break with Communism. Steve was one of the most memorable people I ever met. He was the Political Commissar of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. He played a key role in recruiting American fighters who wanted to combat Franco and Spain. During World War II, he was involved in various kinds of courier activity and other such clandestine work, and after the war he became active in the U.S. Communist Party as an organizer of strikes working with unions in various parts of the country. He became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the United States, only to quit after Stalin’s crimes were unmasked in the Kremlin. He had a vast perspective on the twentieth century and he became the Commander of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.

RE: Describe your odyssey from leaving Truro through working for Michael Dukakis, the Boston Globe, and the New York Times.

SK: I had just been admitted to college when Dukakis ran for lieutenant governor of Massachusetts in 1970. I took time off to work for him. And, after he lost, beginning while I was still a student, I continued working for him through the time when he was elected governor of Massachusetts in 1974. In 1975, I was hired as administrative assistant to the governor. I worked in the State House for a year and then, after some reflection, decided not to pursue a career in government or politics. Instead, I became a freelance journalist, and made my first trips to Central America. I managed to sell some stories to magazines like the Nation and the New Republic, and then the Boston Globe offered me an opportunity to be their Latin America correspondent.

RE: Did you speak Spanish?

SK: Yes. I learned Spanish both in high school and through a summer student exchange program. I was good enough to conduct interviews in Spanish, and I would travel around the hemisphere and return to Boston to write stories. In the early 1980s, Central America became a big story. The New York Times decided to open a bureau in Nicaragua. They needed somebody who had experience working for a big daily newspaper and who was also familiar with Central America. There were very few people who fit that description, so I was hired by the New York Times and began work on January 2, 1983. Soon after that, I was living full-time in Nicaragua. I stayed at the New York Times for twenty-three years, most of it as a foreign correspondent. I had three foreign postings. I was in Nicaragua for six years, Germany for six years, Turkey for four years. Looking back on those assignments, I can see that each one of them placed me at a remarkable historical moment. Central America in the 1980s turned out to be the last gasp of Marxist revolution in the Third World.

The wars in El Salvador and Guatemala and Nicaragua were essentially the last of that kind. So that was quite something to live through, including the intensity of serious warfare. When I left Nicaragua to go to Berlin, I thought to myself, “I’m climbing out of the mud, where I’ve been shot at, beaten by police, and tear-gassed, and now I’m going to be sitting in sophisticated salons with intellectuals, discussing the future of Europe.” But soon enough, Yugoslavia exploded, and I was covering another series of wars. That was a moment of great change for Europe and a very exciting time to be living in Berlin. Then I became the first New York Times bureau chief in Istanbul. That in itself was exciting, but the beat they gave me was also fascinating. In addition to Turkey, I was assigned to cover eight countries that had just come into existence—Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Much of that part of the world had been closed to outsiders for more than half a century.

RE: Did you consider your life as a foreign correspondent to be a glamorous adventure while you were doing it, or when you reflect on it? Or was the reality more drudgery than daring deeds?

SK: My job was quite intense at times and tremendously stimulating. To me, being a foreign correspondent was the greatest job in the world. I got to go to fascinating places and meet the people that you read about in books. I met many people whose lives were very different from mine, and that’s a hugely rewarding experience. Being a war correspondent is not the same thing as being a foreign correspondent, though one is a subset of the other. I went through two cycles of war, one in Central America and one in Yugoslavia. That’s a particular kind of intensity, and I don’t think correspondents who cover war let go of those experiences any more easily than soldiers do. I have seen enough dead bodies, enough blood, and enough crying mothers to last me several lifetimes. I don’t feel a pull to go back to war.

RE: Glad to hear you say that. Let’s talk about your book Reset, a great Middle Eastern history lesson and a discourse on the paucity of creativity in American foreign policy, that was published in 2010. You advocated trying a policy that would focus more on Iran and Turkey, which at the time were the only Middle Eastern countries other than Israel that had experience with democratically elected governments. I’m wondering if you still feel the same way today, and I’m wondering if the US government seeks to pick your brains about foreign affairs.

SK: Reset argues that our traditional foundation for Middle East policy, basing our approach to the region on partnerships with Israel and Saudi Arabia, is outdated, and that Turkey and Iran might make more logical long‑term strategic partners for the United States. When Reset came out, the Green Revolution was underway in Iran and the Revolutionary Guards were beating up people on the streets. The idea that Iran and the United States might have common interests seemed a little bit far-fetched to many people. Now, as the United States and Iran are realizing the strategic value of possible cooperation in the Middle East, and as the cleavage between Saudi Arabia’s interest and America’s interest becomes more and more apparent, there is increased interest in this book.

RE: In the Middle East, events that happened six hundred years ago still seem to have an impact on decisions that are made today. In the United States, we don’t seem capable of adhering to long-term strategies. Do you think this difference in approach contributes to the difficulty of having meaningful dialogue?

SK: Americans like to act in the world as if our actions are not going to have any long‑term consequences. I think the phrase “long‑term” causes many policymakers’ eyes to glaze over. Americans tend to think and act with very little historical memory. Compared to other countries, our history is quite short. The arc of our history is misleading. It suggests to us that it is possible for our country to become forever stronger, richer, and more powerful. That has never happened in history. If you look at countries that have survived over long periods, like China or Iran, you’ll see that they have periods of great wealth, power, and success, and then they have fallow periods. Americans are not used to fallow periods. But it’s important for us to be aware that the world is being reshaped by forces we don’t control.

RE: Your comments are a good transition to your book about the Dulles brothers, The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War. I thoroughly enjoyed reading your book, but I certainly developed a dislike for the Dulles brothers. You made me feel as if almost every problem that we’re dealing with today is an outcome of bad decisions they made in the 1950s. Have you received any feedback from people that thought highly of the Dulles brothers?

SK: I spoke at the State Department and didn’t find anybody who wanted to provide a counter-narrative. You’re right to point out that one conclusion that can be drawn from my book is that many of the huge world crises over the last half century have their roots in misjudgments and bad choices made by the Dulles brothers in the 1950s. The larger lesson is that interventions that violently interrupt the political history of other countries have consequences years and decades and generations later.

RE: You discuss the Dulles brothers’ “white shoe” legal careers, and the huge multinational companies they represented and how they influenced foreign countries in which the multinational companies operated in order to skew their laws in favor of the multinationals. The Dulles brothers did that as lawyers and then continued to protect the interests of the wealthy with the foreign policies they initiated as leaders of federal agencies. There are certainly echoes of the Dulles brothers’ politics and world view in the new Trump administration.

SK: One thing I find interesting about the Dulles brothers is that they embody so much of the American soul and the American psyche and the American experience. I see three forces that are principally responsible for shaping them and their approach to the world. The first is a profound belief in American “exceptionalism.” Allen Dulles and John Foster Dulles grew up under the wing of their grandfather, John Watson Foster, who had been secretary of state during the 1890s. He lived a classic pioneer life in the age of Manifest Destiny. He had gone West, tamed the wilderness, campaigned for Lincoln, started a newspaper, and ingratiated himself with famous men. He came to believe that it was America’s destiny to overspread all of the rest of creation with this new vigor—spiritual as well as material power. He imagined this as applying to North America, but his grandchildren went on to project American power throughout the world in the nuclear age.

The second big force that shaped them was missionary Calvinism. They came from a long line of clergymen and missionaries. They absorbed the Calvinist belief that there are good and evil forces in the world, and that Christians are not allowed to stay at home and simply root for the triumph of justice. Rather, they must go out in the world as missionaries and guarantee the triumph of goodness. If you believe that about religion, it’s a very short step to believing the same thing about politics. There are good regimes and evil regimes, good systems and evil systems—and it is America’s job to crush the evil ones. The third force that shaped the Dulles brothers is the one that you mentioned, their decades of work for a remarkable Wall Street law firm called Sullivan & Cromwell. This law firm had a specialty: forcing small and weak countries to do what big American corporations wanted them to do. The Dulles brothers did this for a living before they came into public office, so they had great experience in pushing around smaller countries.

RE: Another consistent element in your books is the notion that our government lies to us on a regular basis – another theme that can be applied to the new Trump team.

SK: Governments naturally have their own interests, but I don’t think mendacity needs to be accepted as a normal form of public discourse. Over the course of my lifetime, the level of democracy in the United States has clearly declined. We don’t have as much class mobility as we used to have. We don’t have the kind of social cohesion that used to exist. Special interests have used legalized bribery to capture our political system. We shouldn’t take for granted that the blessings of liberty are eternal. History suggests that they are more of an aberration than anything else.

RE: In your Dulles book, there are a series of things that both brothers do that aren’t particularly successful, the Bay of Pigs for one.

SK: You’re putting your finger on one of the main points that I think you can take away from the story of the Dulles brothers. Every single major operation they launched either failed or almost failed. They were very lucky in the last minute to be able to overthrow Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran and Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala. Those were victories by quirks of circumstance after the CIA thought it had lost. After that, every single operation was a disaster. By attacking Nasser, the Dulles brothers wound up making him the greatest hero in the Arab world. They could never get rid of Nehru, whom they hated. They started a civil war in Indonesia because they couldn’t stand Sukarno. They tried to overthrow Fidel Castro repeatedly. The overthrow of Mosaddegh in Iran led to decades of oppression for Iranians and huge trouble all over the world. Guatemala fell into a terrible civil war and endless brutality. The myth that Allen Dulles was a great spymaster and that John Foster Dulles was a visionary wise man of American foreign policy is not supported by the evidence.

RE: This brings to mind the absurdity of the infamous “Mission Accomplished” sign displayed behind President George W. Bush on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in 2003, when in fact the invasion was only the beginning of a 14-year war (and counting).

SK: That’s exactly right. That could be the motto for the Dulles brothers. As an example, John Foster Dulles was more responsible than any other person for the US involvement in Vietnam. He was the head of the US delegation to the Geneva Peace Conference in 1954. As soon as he got there, he realized that all the other delegations were prepared to give a sliver of Indochina to Ho Chi Minh, who had just won his epic battle at Dien Bien Phu. John Foster Dulles couldn’t stand this idea, so he left the conference. It’s the only time in history that an American secretary of state has walked out of a major international conference in the middle. And he went home and told his brother to start a clandestine war in Vietnam. If it were not for that decision by John Foster Dulles, we might have avoided the entire American involvement in the Vietnam War. I can’t even wrap my mind around how different Vietnam and America and the world might have been under those circumstances.

“If it were not for one decision by John Foster Dulles, we might have avoided the entire American involvement in the Vietnam War. I can’t even wrap my mind around how different Vietnam and America and the world might have been under those circumstances.”

RE: The esteemed reputations of the Dulles brothers despite their fiascos reminds me of other politicians who seem to be promoted every time they fail.

SK: I see the Dulles brothers as having made three particularly large historical misjudgments. First, they had no concept of blowback from covert operations. It never occurred to them that their interventions abroad could have terrible effects years or decades later. Secondly, the Dulles brothers were totally opposed to any contact between the United States and hostile rival powers. They thought that any negotiations would dissolve the paradigm of conflict on which the Cold War was based, because it would convey the impression that the Soviets were just normal human beings with whom one could have civilized discussions. By refusing any contact with the Soviet Union and China, Dulles deepened and prolonged the Cold War. The third big misjudgment was that the Dulles brothers totally misunderstood the nature of third-world nationalism. When they saw leaders like Nasser in Egypt, or Lumumba in the Congo, or Sukarno in Indonesia, or Nehru in India, all they could see were tools of the Kremlin.

RE: There’s an old saying about entrepreneurship, “The best decision is the right one. The second best decision is the wrong one, and the worst decision is no decision at all.” When you think about the Dulles brothers and the many wrong decisions they made, it appears to me that the consequences of their wrong decisions were much worse than the “no-decisions” that seem to have happened during the Washington stalemate between a Republican congress and the Obama administration.

SK: The United States was built on what some people call a “can-do” mentality—the idea that if you want something badly enough, and you work hard enough, you’re going to get it. This is an old, wonderfully positive, attitude, but there is also a dark or negative side to the “can-do” mentality. It’s true that Americans have had huge success in confronting obstacles placed in front of them by other people, by nature, by technology, by the environment; but there are certain obstacles, particularly those posed by culture, that are not easy to overcome, no matter how determined you are. Some Americans developed the fantasy that everything in the world is susceptible to our influence. After what’s happened in the world in the last few decades, maybe fewer Americans are instinctively clinging to that belief.

A version of this interview first appeared in Provincetown Arts magazine in 2014. © Raymond Elman.