Finding Purvis Young

“All my life in Florida, you know where the train tracks is: Colored Town….I been used to seeing the railroads. I’m scared that I might go to another part of America and they ain’t got no railroads! [laughs] I love railroads! I put it in my artwork. Railroads. Run-down houses. It’s all in my artwork.”

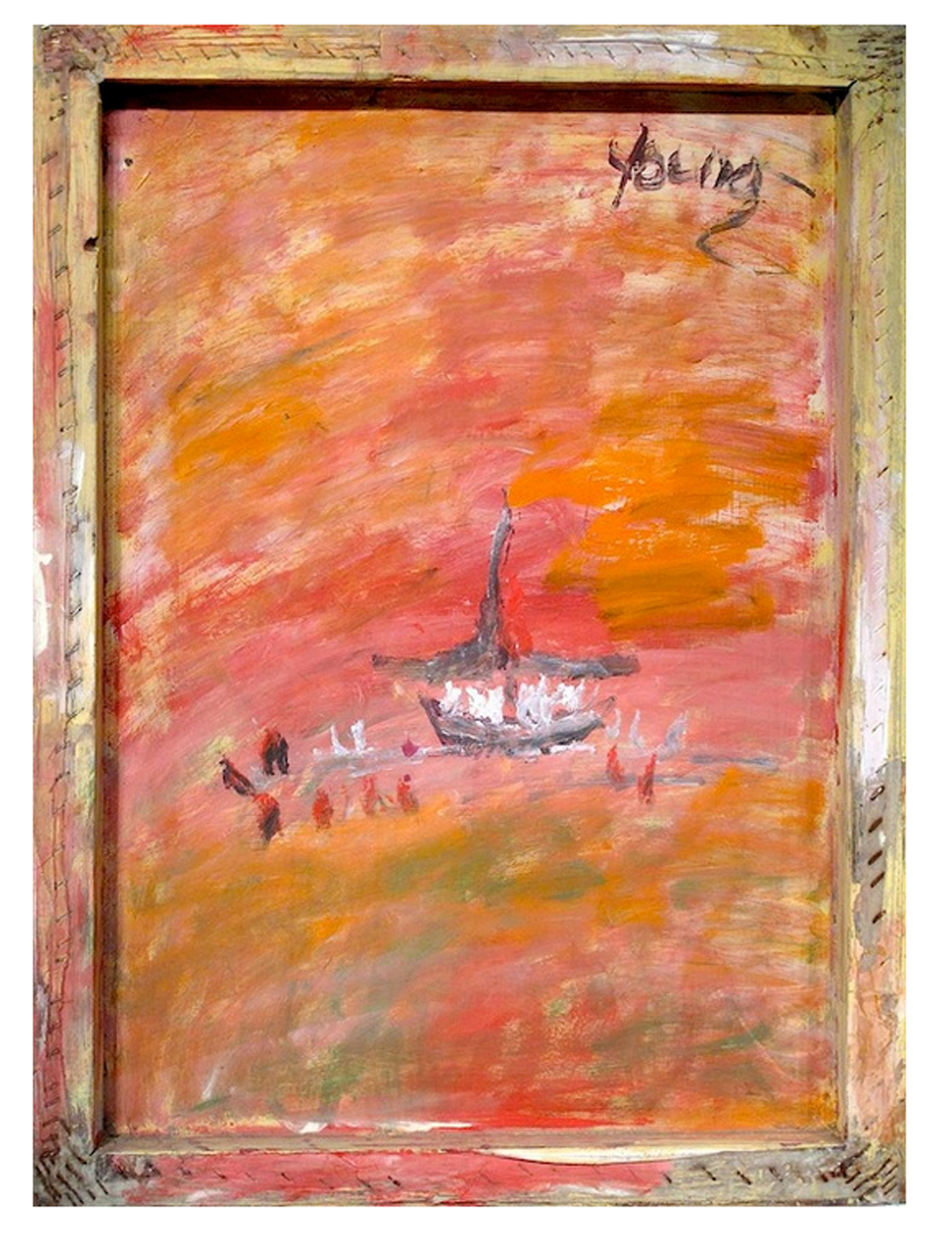

Purvis Young mural, Everyday Life, at Miami-Dade Culmer/Overtown Branch Library. Courtesy: The Vasari Project.

Walk into the special collections archive at Florida International University’s Green Library and ask to watch VHS no. 1568.

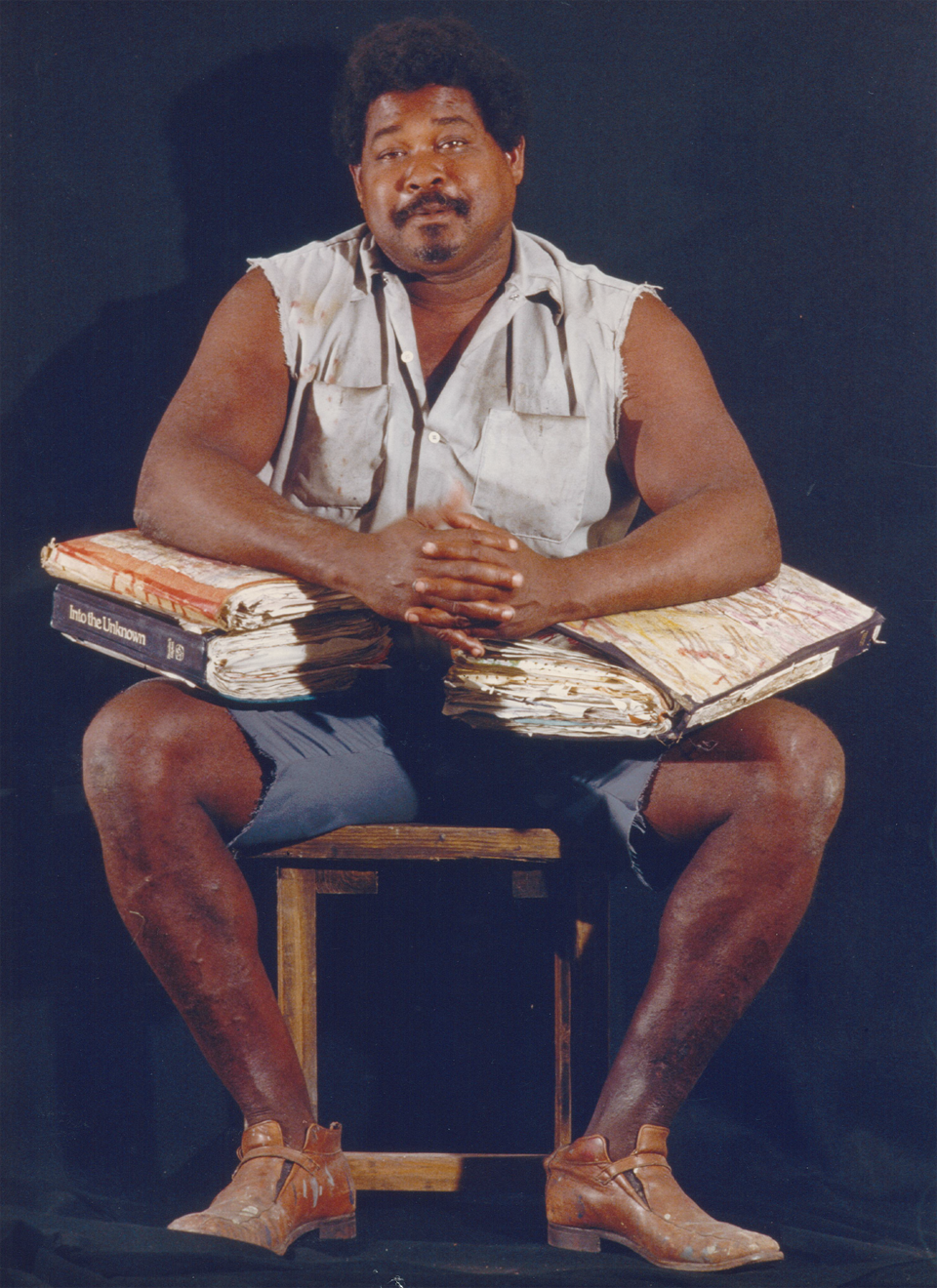

Purvis Young appears in the video, sitting in a familiar pose — slightly hunched over, looking tired but happy, with a green plaid shirt unbuttoned halfway down his chest. He speaks softly and slowly, as always. The camera does not pick up all of his words at first, and it seems as though the audience does not as well. But after a while, the audio improves and his raspy voice is finally fully audible.

“Sometimes I paint royals,” he says, “and I fantasize because I feel like I was a royal.”

With those simple words in the first few seconds of the recording, Purvis Young captivates the audience. The room is silent in the video, both out of respect for Purvis and out of necessity to hear his voice.

“People tell me this – you don’t look like nothin’. But I always look towards the sky and pray: ‘make me famous.’ They don’t know I pray. They don’t know I cry. [pause] Like, most nights I say that to myself.”

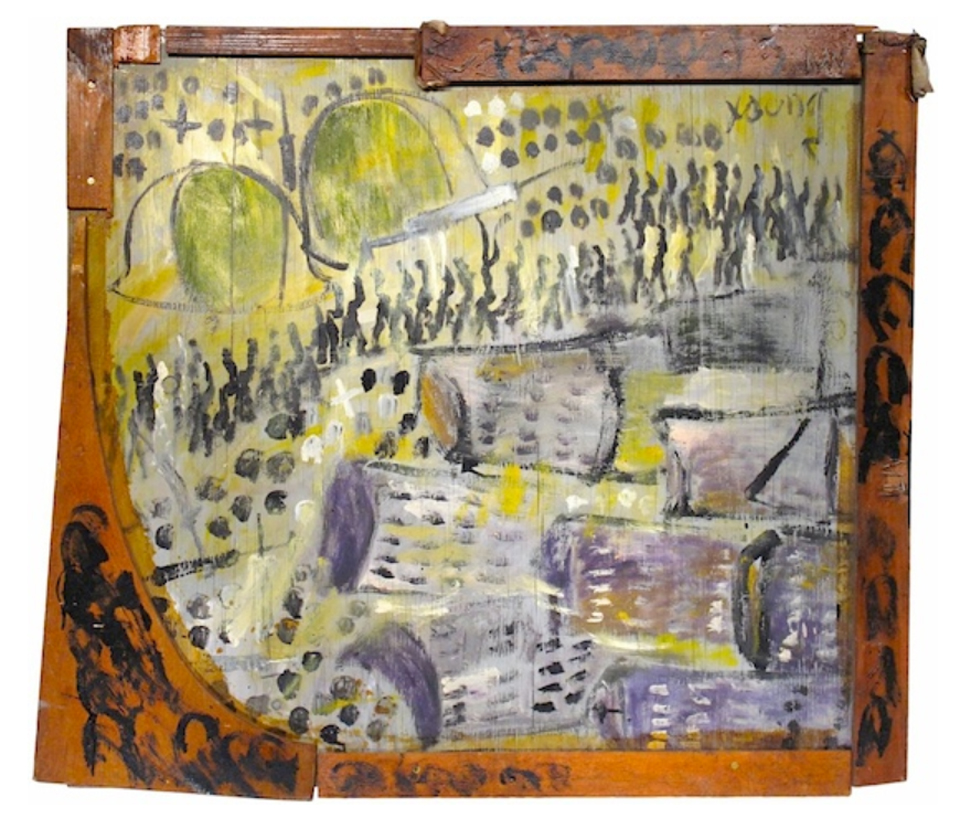

One can find evidence of Purvis all over the Miami area. There is his mural at the Bakehouse Arts Complex, for instance, suffering from sun bleaching and aging. There is a painting of him in the restaurant Kush, just to the right as one enters the door. Almost every art fair in the city has a Purvis piece or two for sale, almost every dealer has held one of his paintings at some point, and if you listen ever so closely, you will still hear his soft voice in the winds around Overtown.

Art enthusiasts in the city of Miami often know some piece of Purvis’ biography – the time he spent in jail, for instance, or his insatiable desire to paint on any surface; his discovery by gallerists/collectors, countered by his financial challenges at the end of his life. There were the highs of having several of his pieces sell at Art Basel Miami Beach, and the lows of having diabetes and other medical issues for years.

But if one truly wants to find Purvis, if one is in search of the source and inspiration for much of Purvis’ work, a trip to the Miami-Dade Public Library is required. It is there that one will find the echoes that remain of Purvis Young.

“You can’t fix all the world’s problems. And sometimes I look up there and say lord how did we get this way. And he tell me, ‘Son, paint it. Paint it.’”

“I met Purvis back in 1976, and we were friends for his whole life. He was one of the regulars in the art and music department back in the ‘80s.”

Barbara Young is a former curator for the Miami-Dade Public Library System (MDPLS). When she met Purvis, she was in charge of the art mobile that went around to different spots in the city with exhibitions, shows, and other activities. She retired in 2005 after decades of work with the library system.

“A lot of artists would come into the library,” she told me. “But Purvis was real special and was somebody that we worried about.”

Barbara speaks of Purvis like a caring godmother — with loving nostalgia and pride. As she flipped through the pages of one of Purvis’ famous notebooks years after his death — books where he would draw and paint images, and then paste them directly into large books — her voice still bore a tinge of concern and worry, as if Purvis might be found in another predicament at any moment.

Barbara kept tabs on Purvis, along with a few others in the library system. They would hold exhibitions of his work and help Purvis get grants and recognition. But they also made sure that he was safe, that he was staying out of trouble, and that he had enough to eat. Little shreds of evidence kept popping up as Barbara and I flipped through the pages of his notebooks. “We did a really nice resume for him,” she said, pulling out an exhibition flyer. “Purvis gave me a few things for safekeeping,” she chuckled when she pulled out a photocopy of his birth certificate. We found a small piece of lined paper with a simple drawing and direct message — I want my money. “One day I came into my office and this little drawing was on my desk. We were still waiting for a grant check to arrive, and Purvis needed the money.”

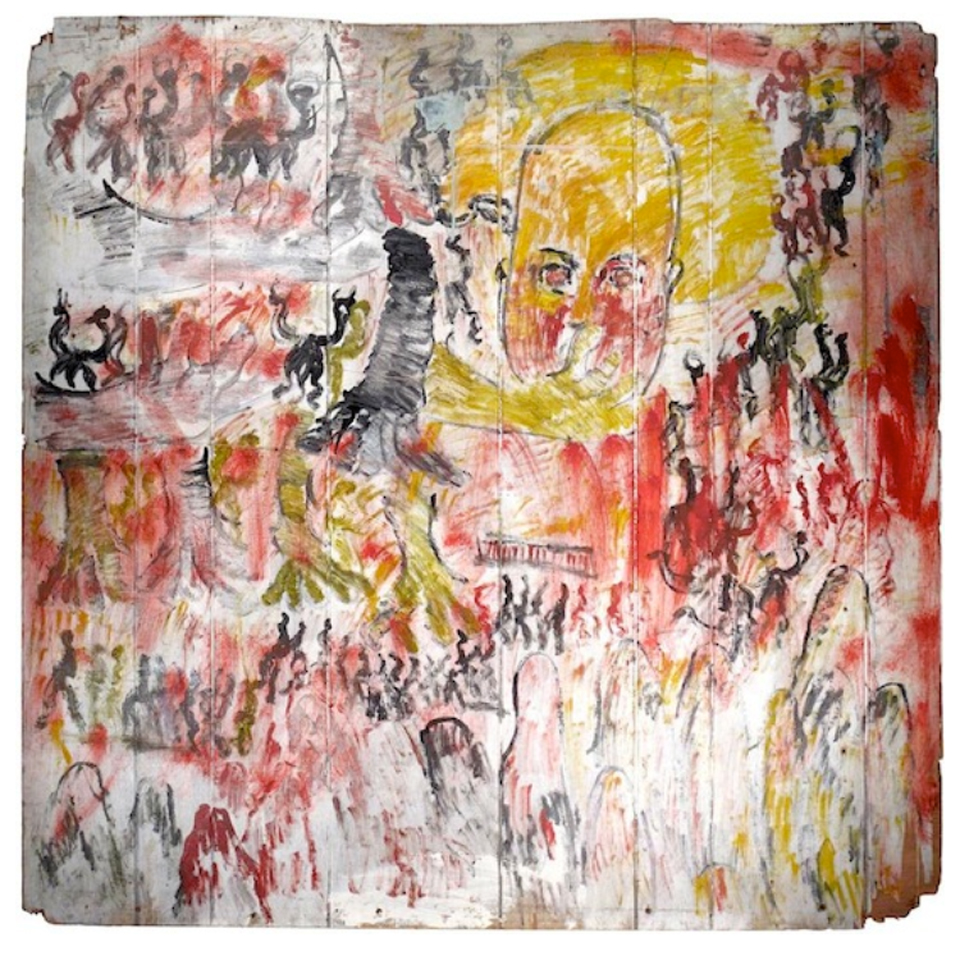

“I looked in the textbooks and seen how much they paint up north. So when I looked in the book and see the Wall of Respect, so I find out it was a way to tell a story with my artwork. I didn’t know you could do that with paintin’. So I just started doin’ me a wall of respect, you know.”

As a good librarian, Barbara was always aware of the importance of collecting and saving even the smallest of details. As a local historian, Barbara put her skills to use for documenting the art world of Miami.

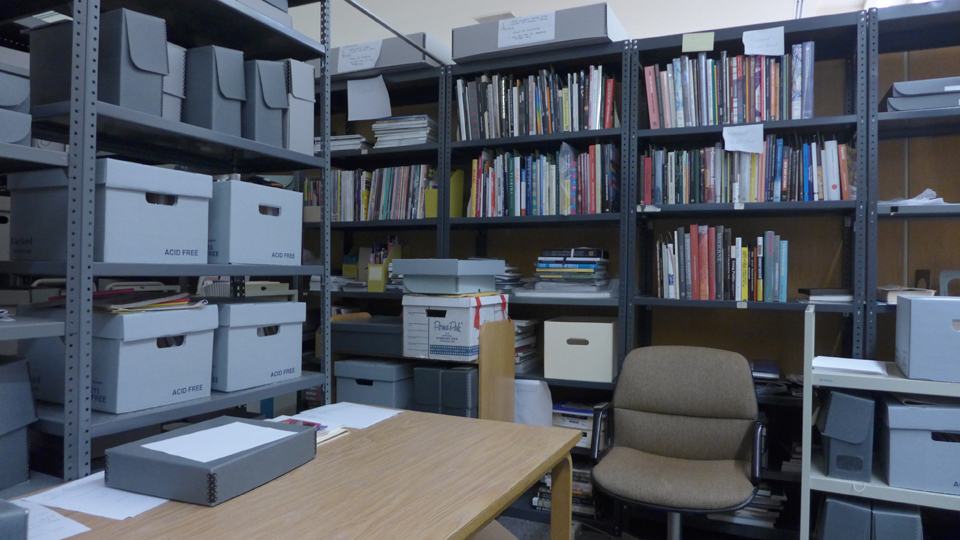

Along with Helen L. Kohen, the former Miami Herald art critic, and a partnership with the Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs, Barbara established the Vasari Project — a project that is dedicated to collecting, documenting, and preserving the history of art in Miami-Dade County from 1945 onwards. Named after Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) — the famed artist-historian whose intricately-detailed book, The Lives of Artists, helped shape the entire discipline of Western art history — this collection holds a wide variety of art detritus. Instead of a collection of artworks (which the MDPLS does have, but in a separate holding), the Vasari Project has photographs, press clippings, exhibition catalogues, oral histories, ads, and many other trinkets and snippets.

These days, the Vasari Project is only open on Saturdays at the Main Library branch on West Flagler Street, but any member of the public can make an appointment to see the collection. “Part of what we do,” said Bill Iverson, the Vasari Project Consultant, “is keep things in the order they come in and stand ready for whatever questions might come our way.”

Want to hold an actual piece of the bright pink material that Christo and Jeanne-Claude used to surround the islands of Biscayne Bay in the 1980s? The Vasari Project has some of it. Want to see what the art world was like before Art Basel? Visit the Vasari Project. Enjoy reading personal notes and journal entries? Have a field day.

When it comes to Purvis Young, however, the Vasari Collection is particularly intimate because of the close ties that the librarians had with him. There are typewritten letters on official letterheads, for instance, that talk about “taking care of his [Purvis’] dental problems.” There is another letter from Greene Gallery, one of the earliest galleries in Miami, that strongly suggests Purvis obtain an independent financial consultant.

It’s all there — a court case printout for felony and misdemeanor; a letter from Celo, Purvis’ close friend, to Barbara; an application for a $10,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts; pictures from exhibition openings; and a plethora of sketches, notes, pictures, and squiggles that Purvis made himself. “I want to work man,” he drew on a sheet of yellow legal pad paper.

In the end, there are several hundred items in the Purvis Young collection, estimates Iverson.

The onslaught of the variety and randomness of the assemblage is overwhelming at first, but a little digging eventually yields interconnections between the items. A set of paint swatches paper-clipped together yield a hint — “walls” is written on the top. Further in the box, there is an official letter about the renovation of one of Purvis’ murals, “Everyday Life”— more clues. The second page lists the paint purchases, which match another set of paint swatches. And finally, there are the receipts for the paint purchases — the final indication of what actually took place.

The Purvis Young collection continues on in much the same way. It would take days to see and appreciate every item that the Library has accumulated from Purvis, and weeks to draw the linkages between each item and Purvis’ life. All of Purvis’ stuff lies in repose in the Miami-Dade Public Library – the final remains of an inspired painter and tortured soul. Purvis’ spirit lives on in his artwork, but his existence lies at peace in the boxes of the Vasari Project.

“I just — I just paint. Maybe the world get better, then I paint better. And when the world quiet down, I’ll quiet down.”