The Paintings of Rodolfo Arellano

The paintings of Rodolfo Arellano are like him – joyful and roaring, but without sacrificing their serenity. The lines are sensual and gentle, never sharp. Each work denotes a long and happy effort with no other aspiration than to participate in the enjoyment of beauty.

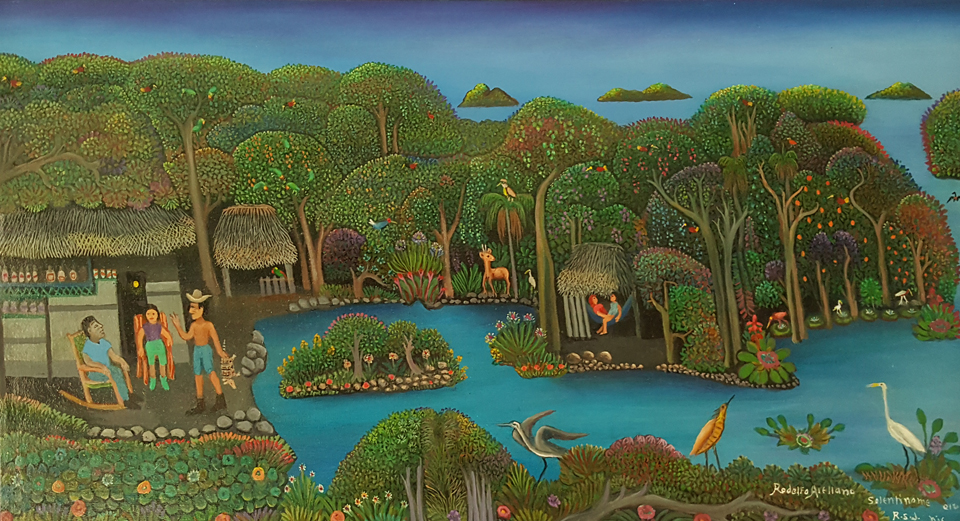

“I paint things as I wish them to be,” he says, sitting in his wheelchair directly across from me. We are in his studio, a modest wooden rancho on the island of La Venada, part of the archipelago of Solentiname in Nicaragua’s great Lake Cocibolca (aka Lake Nicaragua). “I know I am done with a painting when there is nothing wrong, nothing to add,” he says, and smiles humbly to sugarcoat the laconic quality of his statement. A silence ensues, and almost on cue a young woman appears and begins to unveil the different canvases lined up on tables against the walls. The drab room comes alive with colors as vibrant — if not more so — as the flora and fauna of the islands of Solentiname, for those are a big part of Don Rodolfo’s inspiration. The blues, greens and purples are spellbinding. At that moment, as the dark fabric covers are meticulously lifted, one by one, to reveal the painter’s vision of the world, there is a sense of the mystical in the room, which is why nobody talks.

The archipelago of Solentiname itself is considered by many to be a numinous place. Over the course of the past six decades it has become emblematic of Nicaragua’s struggle against oppression, and of the promise of a better world. This is no chimera. In 1966, a contemplative community was formed by Catholic priest and poet Ernesto Cardenal. It quickly became a magnet for those seeking alternatives to the Somoza regime and its support by the traditional church. He created a small community with the peasants of the islands, allowing them to interpret the gospels according to their own reality. “Everyone would gather for a communal meal to which we all contributed. We rowed into Mancarrón from all the neighboring islands, and we ate, and sang, and discussed the gospels,” Don Rodolfo recalls.

Writers and artists also started coming to the islands. It was not an easy task, considering its remote location and its suspect reputation in the eyes of the dictatorship. Don Rodolfo loves to tell the story. “One day, at the beginning of the community, when I was a very young fisherman, a painter by the name of Roger Pérez de la Rocha arrived. He came because he wanted to work in isolation, in the serenity of Solentiname. I observed him painting, and I told him I could do something similar if he gave me the materials. Roger appeared to take me seriously, because he gave me brushes and tubes of paint, and even a canvas, which was something I had never seen before.” By Pérez de la Rocha’s own account, when he saw what Arellano could do, he decided to volunteer to teach the basics of painting to those who wanted to learn. Father Cardenal had the idea that these new painters could illustrate the stories of the gospels. Those became the first “Primitivist” paintings of Solentiname, which in time were used as illustrations in Cardenal’s worldwide famous book, The Gospel in Solentiname. Thus, Solentiname started as a religious, contemplative, community. It recast itself into a revolutionary, religious community along the lines of Theology of Liberation, a budding movement in the Latin America of those times. It became an artists’ colony by chance.

The community prevailed for 11 years, until Somoza ordered its destruction by land and air raids. Most of the surviving members joined the guerrilla movement, some became martyrs of the revolution. The guidance of Cardenal, who was later to become Minister of Culture, led to the creation of a lasting legacy, which was vital to the expansion of the Sandinista revolutionary movement, as well as to sustaining their government subsequent to victory in 1979, and later during the Contra War of the 1980s.

Don Rodolfo did not join the guerrillas, but helped in other ways, like sheltering runaways. They were constantly in hiding. After the destruction of the community in the neighboring island of Mancarrón, locals would keep a lookout for the soldiers who approached by boat. They were not looking for anyone specifically, just spreading terror as a defeat tactic. “It didn’t work,” says Don Rodolfo. “They burned our paintings and our huts, but the spirit of resistance had already been created and there was no stopping us.” Two years later, they were celebrating victory along with the rest of the country. “Paint and other art materials were available again!”

Throughout Don Rodolfo’s fascinating narration, I keep switching my gaze from his eyes that sparkle with the past, to the paintings that seem to prophesize a future. Each picture is meticulously detailed — the leaves of the trees, the different shades of blue of Lake Solentiname, the faces of birds and people. There really is nothing “primitive” about this art.

“They call our painting style ‘primitive,’ ” he says, as if able to read my mind, “but I like to call it ‘intuitive.’ ”

“What is it that your paintings intuit?” I have to ask.

“A better world, a thirst for cooperative spirit and for communion with the earth,” he answers me. “A kind of nostalgia for the future, you could call it.”

“Don Rodolfo,” I say to him, “what I see in your paintings is what I have seen all around Solentiname.”

“You see,” he says with a slightly animated tone, “the intuition works!”