Lightspeed: Art and Technology

Francis Olschafskie wears two big hats: (1) he is a highly regarded fine arts photographer, and (2) he is one of the inventor-pioneers of the computer graphics industry. His latest technological invention, Read and Note (www.readandnote.com), is the world’s most advanced reading, organization, annotation, and collaboration platform. It is cloud-based and works on computers and tablets. Read and Note’s early engagements have been with the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, Cambridge University Press, the Museum of Modern Art, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Untitled, diptych, 2008, photograph, 30 X 50 inches

(left to right) albino snake, Oxford University; Charles Babbage’s brain, London. Babbage is the father of modern computing.

ArtSpeak: Francis, what was the winding path that enabled you to become successful in the divergent worlds of technology and fine art?

Francis Olschafskie: In the 1960s, I was struggling with what I really wanted to do with my life, and I was also struggling with the changing culture of the 1960s, the Vietnam War and the military draft, and all the other things that were going on at the time.

But at the same time, I was really interested in pictures. Like a lot of photographers of my generation, I grew up looking at the big picture magazines like Life and Look, which shaped our world of information, and also shaped the way I saw the world. And I can clearly remember seeing Eugene Smith’s pictures in Life magazine. I remember the series on the country doctor, which is one of my favorites. The series on Albert Schweitzer in Africa. The Walker Evans WPA photographs. And to this day, I can still see those pictures in Life that made me want to be a photographer.

So I started taking pictures. I built my own little darkroom in my closet and I started to manipulate images, trying to emulate Imogen Cunningham. I remember that, instead of putting her photographic paper in a tray with chemicals, she would use a spray bottle and spray developer on the paper. I read about such things in photography magazines, and I became interested in what other photographers were doing.

In 1969, I left college, and I was drafted into the military. They asked me what I did, and I told them I was a photographer. Luckily, that’s what they assigned me to do. I got to do a lot of photography during my two years in the army, and met other photographers as well. The army actually propelled me toward a career as a photographer, so when I got out of the army I went home and told my family that even though I had tried to help out with the family business, and I didn’t want to abandon the family, it was not in me to be a businessman. I couldn’t run the insurance agency that my father left me. I said that I was going to go to an art school. My mother said, “Well, you’re completely out of your mind, so best of luck.” I visited a variety of art schools, like RISD [Rhode Island School of Design], the Philadelphia Art Institute, Rochester Institute of Technology, and I ended up at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (“Mass Art”), where I met like-minded people and had a fantastic experience. When I got out of Mass Art, I was invited to participate in what is now called the “Media Lab” at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (“MIT”), which was a place for interdisciplinary people.

ArtSpeak: How did the Media Lab come to your attention?

FO: While I was at Mass Art, I was lucky to meet Minor White and spend some time with him. Minor White ran the photography program at MIT, and I also got to know his assistant, Jonathan Green, who eventually took over the photography department after Minor’s death. When I was looking to go to graduate school, Jonathan had taken over the photography program at Ohio State, and he offered me a full scholarship and stipend, but I didn’t want to live in Ohio. Jonathan did say to me, however, that there was a program at MIT that would be very interested in the kind of work I was doing. I didn’t really follow his advice, but, as it turns out, someone had mentioned me to Muriel Cooper, who was head of the Visible Language Workshop, which was part of the Media Lab. Muriel was a graphic designer, and she told me that she had noticed my work being exhibited around Boston. At the time, I was the director of a small art school in Boston called Project Art Center, and one day I received a call from Muriel, who said, “I hear you are looking to go to graduate school, and I think you should come over to MIT and talk with me.” So I did. The Media Lab had every type of imaging machine one could imagine, and I was told that I could use all the equipment and do anything I wanted. They had a Heidelberg press, and fifth-generation electrostatic laser typesetters, and the first electrostatic camera, called the Haloid. There was a large (say twenty-by-twenty foot) room, enclosed in glass and cooled to a low temperature, which contained a computer that was capable of manipulating images. I thought, “This is where I should be.”

ArtSpeak: How did you deal with the dichotomy of studying in a science-oriented university, while making fine-arts photography? Did you become a bridge between the two worlds? Is there so much science in photography that there is a natural overlap?

Untitled, diptych, 2009, photograph, 24 x 40 inches

(left to right) Egyptian hand drawing, London; hand in water, London.

FO: I was very intrigued early on by how an understanding of the science of photography can be used to manipulate photographs. It became clear and very obvious to me that I could really refine my images in an extremely unique way by manipulating the chemistry of photography and manipulating the process. And eventually, my understanding and manipulation of the science became more of an aesthetic statement, where I would manipulate until the process was broken. One of my biggest influences, whom I was able to meet and spend time with, was Emmet Gowin, a great American photographer who has directed the photography department at Princeton [University] for the past twenty-five years. Emmet was already doing what I wanted to do, using the chemistry of photography to enhance and refine the image to the extreme. Emmet was the one who turned me on to mixing my own developer, and he showed me how to manipulate my images by expanding the experience of creating the actual object.

This connected for me with what Minor White talked about regarding being a part of the process of making a photograph. Minor used to recommend a little exercise in which you would find a place where you wanted to take a picture in the sun, and lie down in front of a camera in the sun, and feel the light, be part of the moment in the light. People may chuckle at those types of exercises today, but I did those types of things. At the time, it was a really unique way to connect with what you were photographing. On the other side of the process, Emmet would dilute his developer to the point where it took an hour to develop a print, which would expand the range of tone that you could get out of a piece of paper. I experimented with that process as well, to the point where I would leave a piece of photographic paper in developer overnight and come back the next morning, hoping to get as much tonal range as possible.

ArtSpeak: Some photographers prefer to only print what they capture with the camera without any manipulation, while at the other end of the spectrum there are photographers who are deeply engaged in the scientific process of photography, and regard the whole process as part of the experience of making art. How many other photographers were among the group that you were working with at MIT?

FO: I was the only one in the department. The rest of the department was made up of graphic designers, a filmmaker, a sculptor, some painters, and a couple of engineers. The point was to have an interdisciplinary program. The glue that held us all together was experimentation. Even though our backgrounds were in different disciplines, we would all sit around and critique each other’s work, just like in any graduate art program.

ArtSpeak: So how did you go from being at MIT with a photography focus to creating Lightspeed computers?

FO: You may be surprised to learn that in the beginning, Lightspeed, for me, was really about making art. The question of science and art is not a question of either-or. Science has been a big part of making art since inception. What came first, science or art? Stephen Wilson explores the relationship in his book Information Arts: Intersections of Art, Science, and Technology. Artists always confront this issue. They have to become seekers of technical knowledge to expand their art form. Daguerre, a painter who used technology to expand his paintings, winds up being the inventor of photography. Even for the Abstract Expressionists, it wasn’t just about what they were looking at; it was also about something else, like the chemistry of paint or the manipulation of the process.

For example, looking at Morris Louis’s paintings, they weren’t necessarily painted from the front, they were painted from behind. He experimented with and understood what happened when he applied paint to the back of a raw canvas and the paint seeped through to the front. Jackson Pollock was dealing with the space between the brush and the canvas that couldn’t be captured. The painting was the end result of that. When I got out of graduate school, I had no way of making pictures with computers like I had made at MIT, where I had a million-dollar computer to work with. I joined together with a group of people that were developing a computer that would enable them to continue their projects, which ultimately became the Lightspeed computer. My partner, Nathan Felde, was a graphic designer who wanted to be able to continue to do page layout electronically. I wanted to manipulate photographic images.

ArtSpeak: When you were creating Lightspeed, did you also envision creating a company that would develop Lightspeed computers for commercial purposes?

FO: No. I just thought of it as a tool for my own purposes.

ArtSpeak: How did you acquire the knowledge to physically build a computer in the 1980s?

FO: When we were at MIT we used very large mainframe computers, with big sixteen-inch tape drives, and the space had to be air-conditioned at all times. The computers couldn’t be turned off because rebooting them was a big problem. But the times were changing rapidly. After I graduated from MIT, minicomputers were starting to appear, and the basic elements of computers like CPUs were becoming inexpensive. There was a big push to get the minicomputer out and have it take over all of the mainframe work. The 68000 [CPU], which was the basis for the Macintosh, came out as I was getting out of graduate school. When Muriel invited me to attend MIT as an artist, nobody ever told me that to graduate from MIT I would have to take computer-programming classes and computer-science classes. So I ended up taking those classes, and electrical-engineering classes, in order to get out of the institution. But I was lucky to take those EE classes with Harold Edgerton, who was both a photographer and a scientist.

ArtSpeak: What were the dimensions of the first commercial Lightspeed computer?

FO: It was about three feet high by one foot wide.

ArtSpeak: That was pretty small for those times. How were you able to print the images that were created on the Lightspeed?

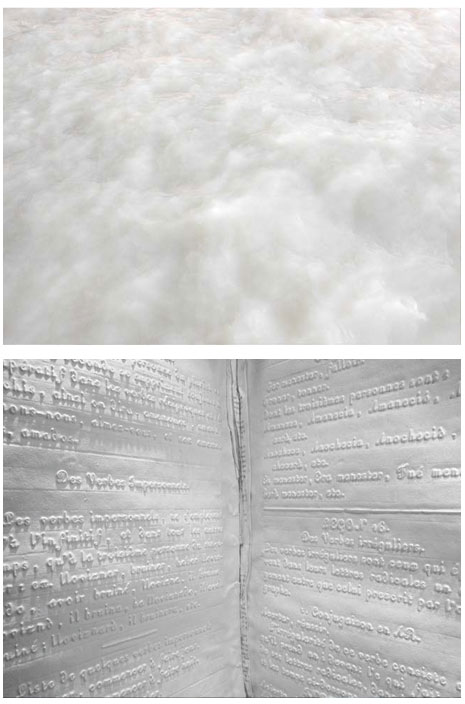

Untitled, diptych, 2010, photograph, 50 x 34 inches

(top to bottom) The white murky waters of the River Thames, London; Louis Braille’s first hand-made touch book, Coupvray, France.

FO: Fortunately, my thesis in graduate school was on output, because it was challenging to print the images that I was manipulating on the computer. When I started at MIT there was no such thing as a color output device, but by the time I left there were a number of them available. And because I was a photographer, and had learned the science of how images are made, I could apply that knowledge to figuring out how to take a colored image out of a computer-graphic system and make a print. Color monitors and color CRTs at that time were like televisions, so they were curved. Not only that, but they had a shadow mask, which is the thing that breaks up the RGB [red, green, blue] projection, and I understood how RGB worked because of my backgrounds in photography and graphic arts and computer science. So I said to myself that there is a way to get computer-generated images onto paper if I can separate them into RGB. At the time, there were early versions of very flat monochrome monitors, and I was able to use a program that allowed me to separate the RGB colors of a photograph and send them as separate images to a monochrome screen. Then I took a photographic view camera [four-by-five and eight-by-ten view cameras], and handheld pieces of acetate (colored red, or green, or blue) between one of the single-color images displayed on the monitor and the camera, and shot a picture onto color film for each of the three colors. Ultimately, that created the full-color image that I was seeing on the curved CRT.

ArtSpeak: And I assume that you simply told people that you created an image on a computer and Boom! Here it is! You didn’t tell people how laborious the process was. You were the proverbial “black box.”

FO: [Laughter] Yeah. I was walking around with a portfolio of photographs that I could describe as “computer-generated,” long before most people.

ArtSpeak: How did Lightspeed transition from a computer workstation that you used to create your photographs into a real business?

FO: Communication Arts magazine, one of the premier graphic-arts magazines, wrote an article about the work that we were doing. The owner of the publication, Richard Coyne, visited us, saw the Lightspeed workstation, and said that he would like to help bring our machine to the graphic-design community. He had the resources to fund that effort, and that’s how our business got started. In the end we were able to sell our machine to many art departments and graphic-design firms.

ArtSpeak: How long did Lightspeed last?

FO: As an ongoing enterprise with my presence, it only lasted for two or three years, because we eventually sold it.

ArtSpeak: What has been your ratio of business to art? When you were at MIT, did you think you would be building machines to solve other people’s needs? Or did you think that most of your time would be devoted to fine-arts photography?

FO: I thought that most of my time would be devoted to making art, and that was all I was interested in doing. But when you are at a place like MIT, the seed is planted in you that you can make something and propel yourself into the business world. And you can be quite successful if you can develop something new and unique. I saw people doing just that. There is a great printmaker named Ron MacNeil, who was one of my teachers. And Ron built a huge, wall-sized, ink-jet printer, funded by corporations, which rewarded him in a variety of ways. I saw a lot of people at MIT doing similar things.

ArtSpeak: Has it been a problem for you to have one foot in the art world and one foot in the business-science world? Have you felt moments of awkwardness when someone introduces you as a participant in two worlds that some would regard as incompatible?

FO: Yes. When I won the Boston Artist Foundation photography fellowship, I was still running Lightspeed, but I partially won the award because of the work I was doing with computers. And I was thrilled to win the award. It was a major achievement. And I remember running from a Lightspeed business meeting to an Artist Foundation awards event, and I showed up wearing a three-piece suit. I ran into a couple of artist friends of mine and their reaction was, “What the hell happened to you?” I was embarrassed. I was wearing a three-piece suit at an art opening . . . and nobody else was.

ArtSpeak: Over the years, you have worked with organizations, like the Daguerre Association in France and the International Center of Photography [ICP] in New York, that have leveraged your unique blend of aesthetics, art history, the history of photography, and technology.

FO: A lot of those projects are a crossover of my being involved in technology and being involved in teaching. I have taught for over twenty-five years. A number of institutions, like the ICP, like the photography department at NYU [New York University], like the School of Visual Arts in New York, were really struggling to integrate new technologies into their photography departments, and due to my hybrid experience, I was provided with opportunities to become involved with those institutions and help launch their digital programs.

After I had been teaching the history of technology and art for quite a number of years, someone suggested that I write a book about it. I’m not a very good writer, but I am a photographer, so I decided to make a photography book about the history of technology and art. I started looking at how photography evolved and the collateral archival material that still exists that I could photograph. I went to Europe in order to stand in the spot where Joseph Niépce made the first fixed photographic image in 1829. I made my trek to Niépce’s house in the south of France, and I made a trek to Henry Fox Talbot’s house; and then I started looking for Daguerre, because eventually Daguerre was considered the father of photography. The odd thing about Daguerre was that there wasn’t anything of his left to be found—there was no Daguerre house, no Daguerre museum, at the time. Daguerre was foremost an artist, yet many accounts of Daguerre refer to him as a scientist, which I always found strange because he was trained as a painter and spent his entire life painting. He had huge successes and huge failures creating dioramas for the theater. The dioramas were transparent paintings, which burned down on a regular basis because it was the 1800s and the stage was lit by open flames. But history has had a hard time calling him an artist first, because he made such an incredible scientific breakthrough. The same might be said of me, though on a less-significant scale. And I find that somewhat offensive to artists.

Searching for material about Daguerre, I remembered a book that I read in undergraduate school, [Helmut and Alison] Gernsheim’s biography of Daguerre, which contained a little postage-stamp image of a diorama Daguerre had made. I knew that Daguerre’s paintings and daguerreotypes were around, distributed in various museums, but there were only something like seventeen daguerreotypes by Daguerre himself still in existence, and it was my understanding only three of them were signed. So I dug out Gernsheim’s book and saw a reference to a diorama that still existed in a very small town called Bry-sur-Marne, which is six miles from the center of Paris.

To make a long story short, I reached out to the mayor of Bry-sur-Marne by e-mail and told him about my research. The mayor responded that yes, there was a diorama by Daguerre in a small church in Bry-sur-Marne, and I said that I wanted to photograph it. He replied, by all means do come over, and have lunch with me as well. So I fly over to Paris, and I am on the Métro to Bry-sur-Marne, when the train breaks down and all the passengers are dumped in the middle of nowhere. Now I have been to Paris many times, and I sort of know my way around, and I can speak a little French, but this situation was outside my comfort zone. Add to that, it’s pouring rain. A torrential downpour. Then they cram all of us on a bus, which is headed to I don’t know where, and I decide that the only thing I can do is go with the flow. The bus goes over a little bridge, and I look out the window and see a statue of Daguerre, which I recognized from the photograph that I had seen in Gernsheim’s book.

So I jumped off the bus into the pouring rain. I am already an hour late for my appointment with the mayor. I make a cell call to the mayor’s office, and suddenly a black SUV with tinted windows pulls up, a woman opens the door and says, “You are going to come and have lunch with the mayor?” I enter the SUV, and there is the mayor talking on his cell phone. We have a wonderful lunch and he and I become friends. He was very interested in exploiting their connection to Daguerre for the good of the city and asked me to help. The mayor had a vision for converting Daguerre’s property into a museum. When Daguerre invented the daguerreotype, he was given a stipend by the king and a large amount of land in Bry-sur-Marne, with a château on it. The château was right across the street from a church, and in his spare time, Daguerre would go over to the church and create his last diorama. When I first saw the diorama, it was in horrible shape. There were holes in it from the war. It was ripped and torn. The diorama is thirty feet wide by forty feet high and stands behind the altar. It’s trompe l’oeil, painted on very thin, transparent canvas, and meant to give the illusion of a large cathedral in this very small Catholic church. It was intended to be illuminated from behind or from the front, so that there could be two different images depending on how it was lit.

Daguerre’s château, which was quite large, had been turned into a hospital for children with special needs. It was a very secluded place, and they wouldn’t let me go in. But the mayor wanted to explore the ideas of restoring the diorama and of creating a Daguerre museum that would be housed in the château.

So I engaged in the project with the mayor and started to help as much as I could, by creating websites, creating donation portals, and things like that. In addition, I introduced the mayor to other people in the United States and we assisted the mayor in applying for funding, and were able to get a $500,000 grant from the Getty Foundation to help restore Daguerre’s last diorama. They had to pull the diorama out of the church and erect a little building to do the work in. They hired restorers who had worked on Versailles. I put up a website and a twenty-four-hour webcam so people could watch the restoration process. The mayor was able to raise money for a new hospital for the special-needs children, and today Daguerre’s château is being converted into a museum.

***

Editor’s Note: A different version of this interview was published in Provincetown Arts magazine in 2012. RSE