A Prophet in Our Own Land: A Personal Reminiscence of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

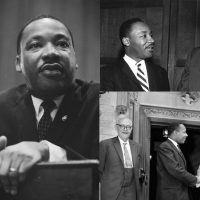

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Dean Ernest Gordon (the author’s father) shaking hands, Princeton University Chapel, c. 1960.

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort

and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy”.

– Martin Luther King Jr.

The day Martin Luther King Jr. died–April 4, 1968–my father was cradling his right hand with his left. Somehow, he’d injured his thumb.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

“Shot!” He shook his head. “Assassinated! Just like that.”

He was weeping, turning his face away from the light. That’s what those men on the street must have been talking about. But I’d been so preoccupied with my own problems at age 15, that I hadn’t understood the gravity of the situation.

“The bloody fools shot him down, a prophet in his own land.”

I will never forget the way he spoke those words that night, trembling with emotion: “A prophet in his own land.”

My father, Ernest Gordon, was Dean of the Chapel at Princeton University and had been corresponding with Dr. King since 1956. He first invited King to preach in the chapel in the spring of 1959, but on September 20, 1958, King was stabbed in Harlem by a crazed woman wielding a letter opener, and he was still in recovery.

I remember the winter of 1960, near the end of January, when King took the train up from Washington, D.C., and we picked him up in our old Peugeot station wagon at the Trenton railroad station. He traveled alone and seemed, to my youthful imagination, surprisingly small and unassuming when he stepped onto the platform wearing a woolen coat and a Homburg hat. I’d heard my father speak of this man and his leadership of the civil rights movement: “For me he is one of the rare prophetic voices in the land,” said my father, but I didn’t really know what that meant.

We took him to our house at 17 Ivy Lane. I remember the roads were icy. My father drove very slowly because we’d been in an ice-related accident a few days earlier, and the back door of the Peugeot was smashed in. My dad tied the door shut with a piece of twine, but it flew open as we rounded a traffic circle near the train station. Dr. King reached out and grabbed me so I wouldn’t fall out of the car.

My mother was standing on the front porch, shivering in the cold, smoking one of her filtered cigarettes. She greeted Dr. King, led him up to the guest room at the top of the stairs, and made sure he was comfortable and had everything he needed. King was incredibly charming and took time to chat about things that my sister and I had interest in. He asked us about school, what books we were reading, and what sports we liked to play.

He then took a nap and came down a few hours later to meet the professors, students, civil rights workers and campus leaders of SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) who had assembled for the evening in our living room.

Sadie Ray, the household cook, was preparing dinner for everyone, but she complained to my mother. Her minister at the First Baptist Church on Green Street had preached in a sermon the week before and inferred that King was a troublemaker, a “self-loathing Negro,” in his words.

At first, Sadie snubbed Dr. King and refused to serve him dinner. My mother was mortified and didn’t know what to do. She just stood there by the swinging pantry door, aghast. Dr. King soon took things in hand and walked into the kitchen, introduced himself and sat at the round table near the stove, eating Sadie’s food while explaining the civil rights movement and the great challenge of the NAACP, a one-on-one seminar, while the rest of the guests sat in the chill of the formal dining room, wondering what was going on back there in the kitchen.

I remember that Dr. King was the sweetest, most humble guest, a friend, a luminous presence, a beautiful voice, right there in the room with you, making direct eye contact while speaking, shaping rhythms with his words, insisting on helping with the dishes after dinner, the center of attention but deferring to others, possessing an inner warmth and sense of love for the everyday as well as the eternal, a soaring figure for any age. But none of us could have understood that yet. (Needless to say, Sadie the cook was forever won over).

The next time he came to visit, in April, 1962, Reverend King preached in the University Chapel right after Dr. Karl Barth, the legendary Swiss theologian. Seventy-five-year-old Barth was the principal author of the “Barmen Declaration” and one of the first public figures in Germany to stand up against the tyranny of Adolf Hitler. While he managed to escape with his life only because of his Swiss citizenship, his friend Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed, hung from a meat hook by Nazi thugs.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dean Ernest Gordon (the author’s father) & Dr. Karl Barth (Swiss theologian ant anti-Nazi), April 29, 1962, standing at the side door of the Princeton University Chapel.

My father felt deeply honored to bring these two champions of human dignity together. King had written his seminary thesis on Barth–“Karl Barth’s Conception of God” (1952)–but it was the first and only time the two great moral leaders actually met. My father himself had survived the Japanese death camps of WW2 and gone on to live his own life as an allegory of forgiveness, so there was a shared sense of sacrifice and fellowship among the three men that day.

After the service, King and Barth came back to our house and sat together at the dining-room table. This time, Sadie Ray was prepared and showered King with love through the food she prepared: scalloped potatoes, collard greens, fried chicken, biscuits and gravy.

Dr. King was supposed to come back in 1965 for another visit, but his schedule didn’t allow it, and he wrote a gracious letter which I recently came across in my father’s papers.

But he would never have another opportunity to serve my father or the Princeton community and three years later he was assassinated, shot down in cold blood. We sat in the living room watching the reports coming through the television screen, Walter Cronkite speaking slowly, as if he were fighting back tears, explaining how King had been shot while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. It happened at 7 p.m. and my father was already on the phone making arrangements to get to the funeral.

My mother drove my father to the emergency room that same night. After taking x-rays, the doctor told him that he’d broken his thumb and proceeded to wrap it with bandages and a metal splint. My father flew to Atlanta a few days later and marched near the front of the procession, near Coretta Scott King, and spent the rest of the afternoon with Rev. King Sr., who told him how young Martin had always seemed to accept his fate, sensing that he only had a short time to live.

Later that week, my father returned to Princeton and conducted a memorial service at the packed University Chapel. He wore a long purple chasuble and you could see the metal splint and bandage when he raised his right hand to make the sign of the cross during the Benediction. “In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy…”

***

These are a few fleeting memories recalled in honor of Dr. King during the week of his birth, when we stop to celebrate his extraordinary life, and his struggle for equality against the forces of racism and repression — especially poignant in this our time of change and uncertainty. May Dr. King’s spirit of grace and compassion serve as our model for confronting the forces of intolerance that continue to haunt this nation.