Haitian Gingerbread

The 1912 Peabody House in Pacot, Haiti survived the 2010 earthquake almost undamaged. Photo: World Monument Fund.

Rain is pouring down in Little Haiti. The colorful storefronts are bathed in a torrential downpour. Inside the Little Haiti Cultural Center, people are taking cover. The halls are echoing with the bustle of children’s activities. The gallery space inside is a long nave, where warm Miami light floods in through large floor-to-ceiling windows, evenly spaced along the west wall. The windows drip with fresh rain and the air inside is thick with an intoxicating tropical humidity.

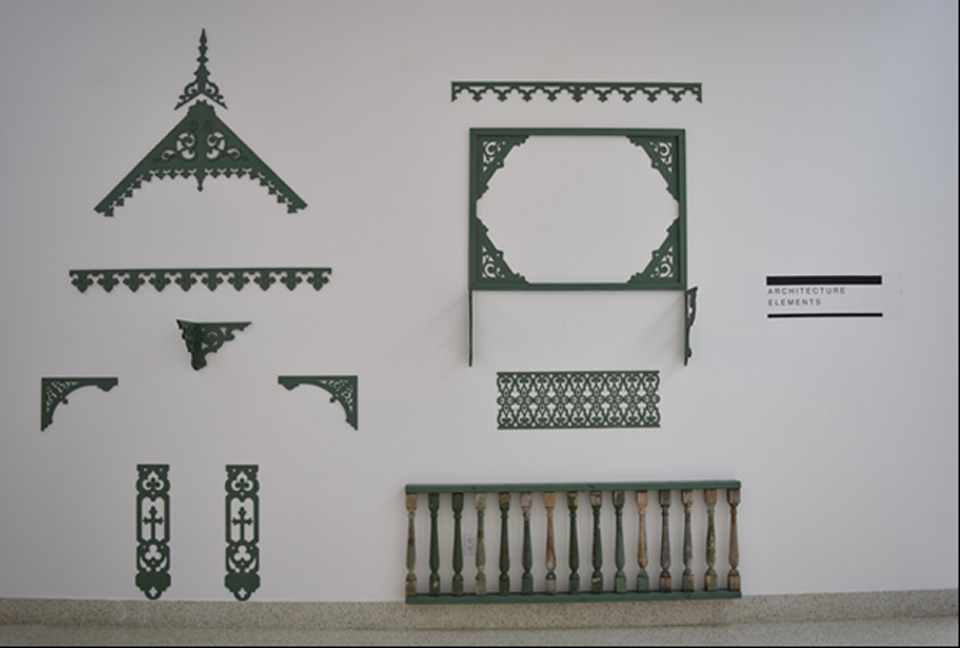

The gallery exhibition is comprised of architectural relics and illustrations. These include photographs highlighting architectural “gingerbread” elements of structures built in Haiti dating back to 1881, drawings by Angeline Phillips illustrating specific components, and pragmatic black-and-white diagrams. The exhibition also includes delicate pieces of ornamentation: weathered and chipped green painted details like frames and railings hang on the wall and soak up the natural humidity of the space.

Architectural ornamentation commonly featured in the gingerbread style. These are fine examples of lace motif, repetitive patterns, and a wooden baluster (bottom right). Photo: Claudia & Gustavo Garcia.

I spoke with Gustavo and Claudia Garcia, the curators of this exhibition, about the history of the iconic Haitian gingerbread houses — as well as the current state of Haiti, which is still very much in the process of rebirth and rebuilding, following the devastating earthquake of 2010.

Camila Miorelli: Your family is from Cuba. What is your connection to the Haitian community?

Gustavo Garcia: Claudia and I started working in Haiti in 2010, helping a friend who happens to be a priest who was, and still is, living in Haiti. He’s a Nigerian missionary and he built a church in Haiti which was destroyed by the earthquake. It’s a sad and dramatic story. Our friend raised the necessary money and built the church. A couple of days after he paid the last painter, the earthquake struck and everything tumbled down. That’s when we started engaging with Haitian architecture. The situation in 2010 was horrible, but Haitians are very resilient and they will not stop striving to attain some sort of normal life.

My family migrated to Miami from Cuba. Haiti and Cuba are right next to each other in the Caribbean, so we share a sense of geography. Many Cubans were involved with Haitian humanitarian efforts post-earthquake. The main connection for me and Claudia started through God’s Providence, a charity. Through missionary efforts, Claudia became involved with immediate relief efforts. Claudia and I competed for “Building Back Better Communities” and were selected as finalists, however the competition was not fully funded and none of the buildings were built. Since Claudia and I have architecture backgrounds, we decided to see how we could help on our own. So we started Pari Passu Foundation, which is concerned with sustainable architecture. We also started a summer camp in Haiti, which we have continued over the past years. Architecture is in our DNA.

CM: Why did you decided to organize and curate an exhibition of Haitian architecture?

Gustavo: There has been an ongoing conversation about whether there is a Haitian architecture beyond an architecture of necessity.

The National Palace is no longer in existence, the Cathedral is no longer in existence, and everything was destroyed by the earthquake. We asked ourselves: Is there a distinctly Haitian architecture that could become a symbol of national pride? The “gingerbread houses” are a glimmer of hope, together with sustainable architectural construction, they tie together over 100 years of history, and tie together the spirit of the nation. There is a set of plans for rebuilding a nation that is seeking a new narrative.

We hope to take this exhibit to some other places, perhaps back to Haiti.

CM: How did the gingerbread style of architectural adornment evolve in Haiti?

Claudia Garcia: An earthquake hit Haiti in 1770 and another in 1842, which destroyed much of the mostly wooden homes and buildings. After the 1842 earthquake, city officials stipulated that construction had to be in masonry and concrete due to new fire regulations. Post-1925, there was a trend to develop different building styles because of changes in available materials, which included wood, concrete, and masonry. After the 2010 earthquake, in which a lot of emblematic buildings of gingerbread style like The Palace were destroyed, people reconsidered traditional homes that were still standing amidst the rubble. The World Monument Fund (WMF) took notice and elevated restoration of traditional gingerbread construction.

Gustavo: To understand the importance of the gingerbread houses we have to look at a little bit of Haiti’s history. Haiti has always been part of the international community one way or another. There is no other island in the Caribbean that is divided into two states. The Haitian side of the island has a French history. It’s not very clear where the term “gingerbread” comes from, but according to historians and the World Monument Fund, it was adopted by American tourists who visited the island and called it “gingerbread” for lack of a better term. What they knew was the American gingerbread style, which comes from the Victorian style, which is Gothic architecture.

These gingerbread homes have been around for hundreds of years. There used to be a bad connotation to this style, because of associations with colonialism and the elite, but the way they are rebuilding, post-earthquake, negates some of those negative connotations.

The homes that are being rebuilt now are crazy, they are huge mansions, especially in Pétionville, which is at the top of a hill. Now, even the poorest of homes have a baluster balcony. Or they have some type of woodwork imitating at least one element of the gingerbread style.

In the exhibition we present a breakdown of the gingerbread elements. It was important to us to delineate the architectural elements and separate them from their historical context.

Claudia: The architectural ornaments were used on all kinds of buildings: homes, places of worship, government buildings.

CM: In what ways has Haiti accepted and rejected outside influence?

Gustavo: When the Victorian architecture style came to Haiti from England and France, it was propagated everywhere. Many times the elements were developed from templates. Carpenters would select a template from an architecture book and reproduce it. As a parallel to music, it’s like the scoring sheet; for the first time it allows a composer to write in a particular style and replicate it over and over again. Gingerbread ornamentation happened in the same way and is manifested throughout Haitian society.

Claudia: When Haitian architects went to Europe to study, they returned to Haiti and made the elements they observed in Europe — projecting these new styles onto their own culture. The colors, the type of fret work, the lattice work, all started taking on a different tone translated into the Haitian culture.

CM: How does this tie into rebuilding Haiti and maintaining cultural integrity?

Claudia: As a result of the earthquake in 1842 there were changes made in the materials used to build homes. Now, because of the 2010 earthquake, they are seeing that the changes made in 1842 were actually detrimental to the earthquake resistance of the homes. The concrete they used, the new materials, were not effective when it came to earthquake resistance or prevention of crumbling. At least not as effective or stable as homes built in the gingerbread style, which have stood for hundreds of years.

The gingerbread houses used to represent the elite and the bureaucratic. Looking at these homes is looking at Haitian architectural history and as it turns out, it is still the best design option for Haitians to rebuild in a way that is characteristic of their country.

CM: What is the relevance of the gingerbread style to Miami and Little Haiti?

Gustavo: It’s important to be aware of the gingerbread style because elements from that architecture have been reinterpreted in Miami. For example, the Little Haiti Cultural Center is owned and operated by the city of Miami, but includes elements borrowed from the gingerbread style. If you look at the gallery you will see a resemblance to the gingerbread style.

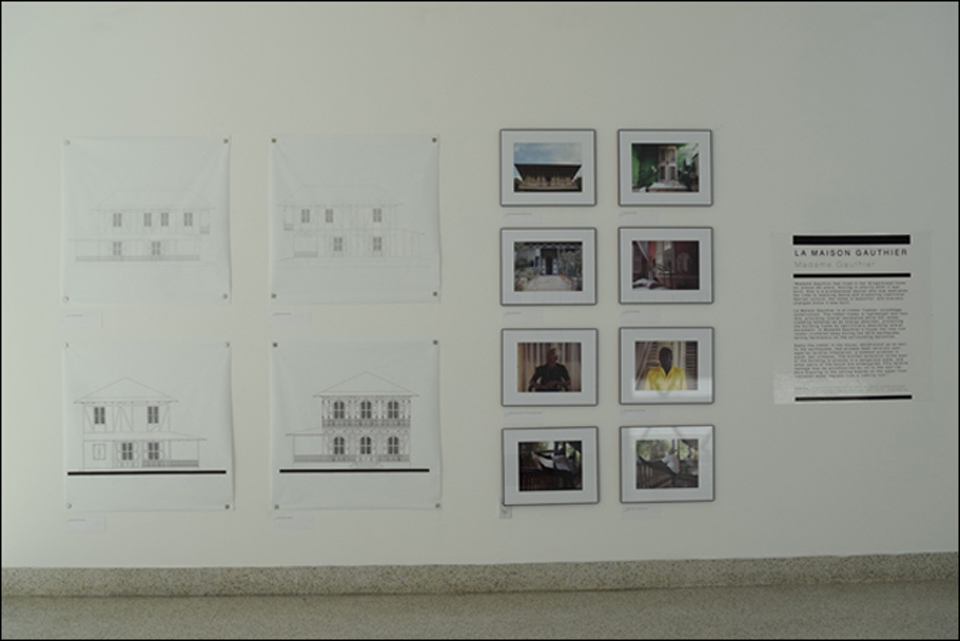

A section devoted to dancer Vivian Gauthier, one of the most famous residents of the gingerbread houses. Photo: Claudia & Gustavo Garcia

Claudia: Some examples of gingerbread style in the Little Haiti Cultural Center are the pitched roofs and the hurricane shutters, which imitate lattice work. This very contemporary building was designed by Zyscovich Architects.

Gustavo: What is important to note are the sustainable components which are not only ornamental but also functional.

Claudia: Exactly, like the double-pitched roofs, and stack ventilation, as well as the high windows and openings for cross ventilation. There are also big porches and verandas that offer shade and protection from tropical weather.

Gustavo: An interesting thing about the porches in gingerbread houses is that they bring private life into an in-between space: semi-outside, semi-inside.

CM: What are the specific examples of gingerbread themes and application in the exhibition?

Gustavo: In the exhibition we present the house of Vivian Gauthier (b.1918), a very famous Haitian dancer, who has lived in the house since 1932. Her home was converted into a dance studio for her dance company.

Gauthier trained generations of dancers. One of the dancers performed at the opening reception of this exhibition.

Private rituals take place in these types of gingerbread houses, for example, drum ceremonies and specific voodoo practices.

There is always something going on in the generally large gingerbread houses. This is in direct contrast with the slums of Port-au-Prince, like Cité Soleil, where the spaces are so cramped that they are not conducive for group ritualistic practices.

Following the 2010 earthquake there were many different ideas regarding what type of buildings should be built. For example, one idea focused on ultra-efficient container homes. But none of the ideas have embodied the spirit of Haitian heritage (private life spilling over) like the gingerbread house. The new homes have to include an intermediate space that is semi-private.

CM: So Vivian Gauthier’s house is an example of pre-earthquake architecture that’s still standing after the 2010 earthquake?

Gustavo: Yes. Her house has survived for hundreds of years and she still lives there.

Claudia: The great thing is that Vivian has been inhabiting the same home for almost a century and she is still capable of maintaining a private life that includes social aspects.

Gustavo: We have a photo of a dancer doing his stretch work on the baluster of Gauthier’s house. What’s interesting is that it’s not like stretching at a barre in a modern dance studio. In Gauthier’s gingerbread house space the dancers use available architectural components.

CM: What did you take into consideration when putting the exhibition together and organizing the gallery space?

Gustavo: There are socioeconomic and political elements to the Haitian heritage which sometimes conflict with one another. Yet they are also emblematic of Haitian resilience and how these homes have come to represent the nation — because Haiti’s still there and the people are still there.

The language of architecture is very specific and detail-oriented, and that’s why we have aimed for black-and-white simplicity in the way we have displayed most of the drawings, photographs, and artifacts. On one wall there is a display of black-and-white drawings by Anghelen Phillips, which was published in her 1975 book Gingerbread Houses: Haiti’s Endangered Species. From 1971 to 1975 she made drawings that document gingerbread houses. She made illustrations of more than forty homes in the neighborhoods of Port-Au-Prince. Phillips is also developing awareness of the importance of preserving these homes. Yet, little by little, fewer and fewer of the homes are still standing.

Drawings by Angeline Phillips line the east wall leading down the nave. Photo: Claudia & Gustavo Garcia.

CM: In the gallery there are drawings, prints, and fragments of architectural ornamentation. How did you collect the artifacts for the exhibition?

Claudia: It was a lengthy process. One of our main resources was the World Monument Fund.

Gustavo: The WMF connected us to a variety of photographers, architecture magazine editors, researchers, and urban planners.

There is no official gingerbread house book, there is only archival information. So we spent a year compiling information, drawings, and maps. The problem is a lot of the pictures were of very poor quality and a lot of documentation was lost in the earthquake. We did a year of research at the Library of the Caribbean at Florida International University (they have digitized a lot of Haitian national archives), and we gathered roughly a thousand images and texts.

CM: How did you customize this exhibition to Miami’s Haitian community?

Gustavo: The subtitle of the exhibition is “Haiti’s Living Architecture.” So we had to tie that theme into our exhibition choices. On opening night, we showed a video of dancers in Vivian Gauthier’s gingerbread dance studio.

One problem is that you can put a thousand historical images on the wall, but they will never tell the full story or convey the importance of the gingerbread houses. One of the most interesting experiences has been communicating with visitors to the exhibition who grew up with the gingerbread houses and have their own stories to tell.

Claudia: They start reminiscing about their experiences and open up with their stories. There’s one picture that’s a shot of the kitchen and the bedroom in the house of Vivian Gauthier. A lot of people have told us, “That reminds me of my old kitchen.”

CM: What were some difficulties you encountered?

Claudia: There were three major obstacles: (1) condensing so much information into a few select images, (2) obtaining high-quality images, and (3) the challenge inherent with every exhibition — obtaining usage rights.

It was also challenging to create the right balance of photographs, drawings, and ornament. A nice range would include exterior shots, interior, technical drawings, and pieces showing the essence of the architecture. All this while trying to show the different facets of the gingerbread style and the homes themselves.

Gustavo: When you are curating an exhibition, you design for a specific space. The gallery at the Little Haiti Cultural Center was challenging because it’s very long and narrow. It’s a nave with double-height ceilings. And when you explore the space, it’s in a processional manner. You start at the beginning and walk towards the end. It was challenging to tell the story in as few images as possible, and in a very simple way, for the biggest and broadest audience.

The audience included first generation Haitians who were born in Miami and have never been to Haiti, and older people with strong memories of Haiti.

CM: Do you think the average Haitian sees gingerbread houses as a metaphor of Haitian life and resilience?

Claudia: Absolutely, there is a direct correlation between the gingerbread style and the people of Haiti. The fact that these buildings withstood earthquakes and other disasters is a testament to their lineage.

Gustavo: People don’t stop living just because they live in poverty or misery. Within their world they have their own set of aspirations, their own set of challenges, and their own lives. The solution to escaping poverty should not be to migrate to another country, which many poor people have done.

On the other side, you have these gingerbread homes, built over 100 years ago, which have managed, with very little financial resources, to continue to exist. The National Palace is gone, the Cathedral is gone, but new institutions like the hospital in Mirbalais are emerging.

Claudia: The human condition in Haiti has been consistently challenged throughout Haiti’s entire history. Whether it’s natural, like an earthquake, or manmade, like political oppression. Yet the Haitian people are still working to rebuild their nation, socially and physically. The gingerbread homes have a symbolic value, the homes will be rebuilt as the nation rebuilds itself socially and spiritually.

Gustavo: Think about this, two generations of father and son oppression, two dictatorships, one worse than the other, Papa Doc and Baby Doc. Toss in very little economic support for the gingerbread homes, the physical devastation of hurricanes and earthquakes, and yet the houses are still there! And so are the people. ♦